2020-10-28

There are tasks, such as understanding visual scenes, that we do so often that we don’t realize how difficult they are… Until we try to solve them in robots and other artificial systems. So perception is non-trivial, and this means that a designer’s goal doesn’t always agree with the organism’s “meaning of life”.

Like gravity, our perception is so omnipresent that we hardly notice it. So, it’s easy to assume that perception takes little effort. It’s not until working with a robot’s perceptual system or image processing that one develops an idea of how difficult perception is. The task of simply identifying the objects in an image can be tricky (and despite “super human” performance on some benchmarks, computer vision is still unsolved for more involved tasks like complex scene understanding). This is because, fundamentally, perception is a problem of “Squiggly Lines”.

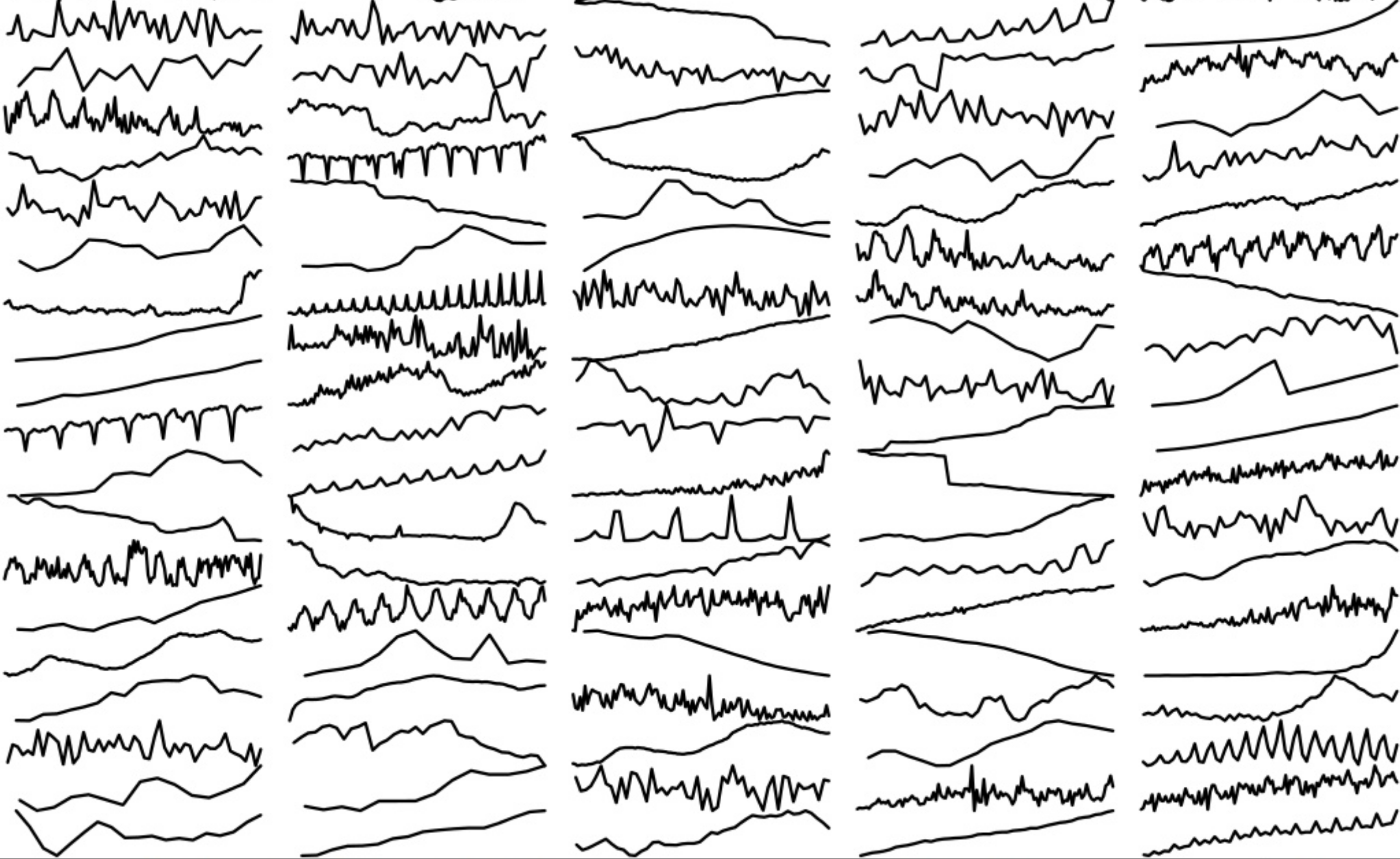

To illustrate what’s meant by a problem of “squiggly lines”, suppose we wanted to create a robotic bumblebee. Also suppose that we were given the bee’s body and we just had to program its “brain”. The bee’s compound eye is really just a set of light-sensors (called ommatidia). Basically, each “surface” (or ommatidium) reports a value proportional to how much light is striking it (and different surfaces might be sensitive to different colors or angles). Unless we explicitly “tell” it, our robotic bee doesn’t know what its sensors mean. It just has the sensor readings over time, which look like a bunch of squiggly lines if you plot them out. That is, each of the bee’s several thousand receptors reports a signal, which can be plotted over time. So, the bee’s brain’s input can be viewed as several thousand aligned plots.

Suppose I gave you plots of these sensors’ readings, but I didn’t tell you which sensor was which. Suppose I didn’t even tell you that these are light sensors from a robotic bumblebee’s eye. As far as you would know, these could even be readings from a simulation of a mobile robot in a 5 Dimensional world. From this perspective, it’s difficult to tell the difference between the squiggles produced by a flower and the squiggles produced by a female bumblebee. The bumblebee’s perceptual system has two limiting factors: That of the distinguishing ability of the bee’s compound eye. If a bee’s vision is hopelessly blurry, then no amount of processing will be able to distinguish a flower from a female bee. The second limiting factor is that, even if the bee’s vision is high resolution and crystal clear, a significant amount of computation is needed to tell the difference between a flower and a female bee. Although it’d look silly, we could give the bumblebee human eyes, but there would still be the problem of processing all that data. The bee’s tiny brain couldn’t do it. It’s worth noting that our own visual processing system, the visual cortex, is many times the mass of a bee. The human visual cortex has around 140 million neurons per hemisphere, while a bee’s entire brain is about one million neurons.

The Bumblebee Orchid takes advantage of the limited perceptual systems of male bumblebees. Its flowers “look” and smell like fertile female bumblebees. That is, the flowers have the rough shape and coloring of female bumblebees, but other than that, they don’t actually look very much like female bumblebees. (I can’t say how similar they smell like them.) With a glance, a person can easily tell the difference between a bumblebee and a bumblebee orchid (though I have trouble telling males from females because of my limited olfactory perceptual system). However, they’re good enough to trick the “low resolution” compound eyes and tiny brains of the randy males, and the male bumblebees attempt to copulate with the flower, picking up and dropping off the flower’s pollen so that the flower can mate successfully.

The perceptual system and brain of a peacock (or a peahen, the female version) are much more sophisticated than that of a male bumblebee, but these systems are still limited (as are ours!). Bird’s perceptual systems are particularly good at finding eyes. A number of butterflies and moths such as the Common Buckeye Butterfly, and the Promethea Silkmoth take advantage of this by having eyespots (because eyes are a giveaway that something is animate). These spots look a lot more like owls’ eyes than the bumblebee orchids looks like bumblebees, but a person can still easily tell the difference between one of these moths and an owl. (Birds might actually be able to tell the difference if they look hard, but they might not stick around long enough to do that. Just in case.) So, I assume that, like other birds and even some insects, peahen’s brains are good at recognizing eyespots. That is, eyespots have a special place in the perceptual system of peahens. So I’m guessing that eyespots are so prevalent on peacock tails partially because of their special place in the perceptual systems of peahens.